The mysterious case of the plus-size clothing consumer.

I was standing in the aisle between cubicles when I turned my back, gritted my teeth and said, rather shortly, “No, really, you can check the tag on my pants if you don’t believe me.”

I’d made a casual comment about not being able to find black slacks that I liked, and a well-meaning but oblivious co-worker had just suggested that I shop at Nordstrom Rack. When I responded gently that Nordstrom didn’t really carry my 26/28 clothing size and probably wasn’t worth the time to visit, she’d insisted that I couldn’t possibly wear a 26/28 in the first place.

Reader, she declined the offer to check in my pants.

Leaving the issue of our cultural inability to accept that anyone could be that fat aside:

Sixty-seven percent of American women wear plus sizes, but only 16% of new clothing is made for them. What’s behind this mismatch? Where is all the inclusive apparel? How did we get here?

Some depressing statistics (all sourced from this Racked article):

- The retail analytics firm Edited looked at 25 of the largest multi-brand retailers (think Shopbop, Macy’s, Net-a-Porter, etc.), which together carry more than 15,500 brands, and found that just 2.3 percent of their women’s apparel assortment is plus-size.

- Of 300 or so brands that showed at New York Fashion Week, only 32 offer up to at least a size 16, and 14 produce sizes 22 or above. Plus size makes up just 0.1% of the luxury market.

- For online retailers that carry both plus and straight sizes, the figures are only somewhat better: Overall, 16 percent of their assortment is plus.

When you do not live in a big body, it is almost impossible to understand the scope of the problem. Here’s a helpful graph:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11480743/NORDSTROM.jpg)

At a size 26/28, I live in that tiny purple margin. I live in the 16%. When I need clothing for the office, for fashion, for fun, for athletic activities, I have to hope that somewhere, some retailer decided that the pieces I need should be part of that 16%. (Ask me about the Land’s End fleece hoodie I have worn to death and cannot find a replacement for because no one else makes anything just like it and Land’s End discontinued it.)

This is where the discussion about plus-size clothing usually breaks down into a number of protestations: But larger sizes use more fabric! But brands would have to charge twice as much for them! But it’s hard to design plus-size patterns! But but but!

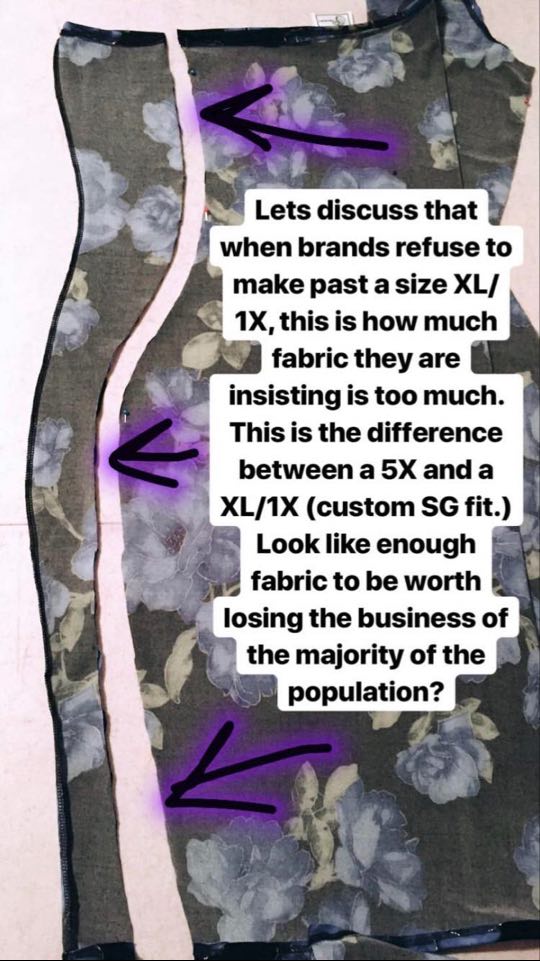

It’s true that larger pieces of clothing use more fabric, but not as much as you’d think. Inclusive clothing brand SmartGlamour‘s Mallorie Dunn breaks it down:

Though larger pieces of clothing do indeed use a small amount of additional fabric, the “brands would have to charge soooooo much more for them” argument is weak. The reason you don’t see companies charging more for a size 10 than they do for a size 0 is that that cost is already averaged out among all the sizes of that style. Averaging in the cost of larger pieces might make a thin consumer’s garments cost a few pennies more (or a few dollars, on the high-quality end). That’s not too much to ask.

When you see pieces that cost more in plus sizes (here’s looking at you, Old Navy), that’s a fat tax: a surcharge fat consumers are forced to pay because our options are so limited.

It’s also true that plus-size patterns are more difficult to design and execute properly. As bodies increase in size, their proportions grow more exaggerated as well. You can’t just create larger sizing by blowing up a straight-size pattern on a copier; you have to account for the changing proportions.

Overcoming them requires investment, but so does becoming an apparel purveyor in the first place. Hundreds of small and indie businesses have figured it out, as have a few fashion behemoths. Creating a truly inclusive clothing line (up to a 10X/size 40, with custom sizing for more upscale lines) requires resources, will, and marketing power — all perfectly doable for American clothing brands.

But here’s the crux:

If the majority of the clothing market consists of large bodies, why are small bodies the default? Why is it assumed that a brand will begin by clothing small bodies, and maybe someday extend into larger sizes? Why does almost every designer on Project Runway moan and groan when forced to design for and dress a person who has a body closer to the average size of the population?

Why is it assumed that it makes the most sense to target a smaller portion of the population? Why throw away the largest part of the market — plus sizes — with the smallest amount of existing competition?

Why are dozens of apparel companies, from Victoria’s Secret to Forever 21 to Nieman Marcus, declaring bankruptcy while only offering products to a third of women?

It’s almost like there’s some sort of…stigma involved.

Let’s dig deep.

Every Monday, I send out my Body Liberation Guide, a thoughtful email jam-packed with resources for changing the way you see your own body and the bodies you see around you. And it’s free. Let’s change the world together.

Hi there! I'm Lindley. I create artwork that celebrates the unique beauty of bodies that fall outside conventional "beauty" standards at Body Liberation Photography. I'm also the creator of Body Liberation Stock and the Body Love Shop, a curated central resource for body-friendly artwork and products. Find all my work here at bodyliberationphotos.com.

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline

- Lindley Ashline