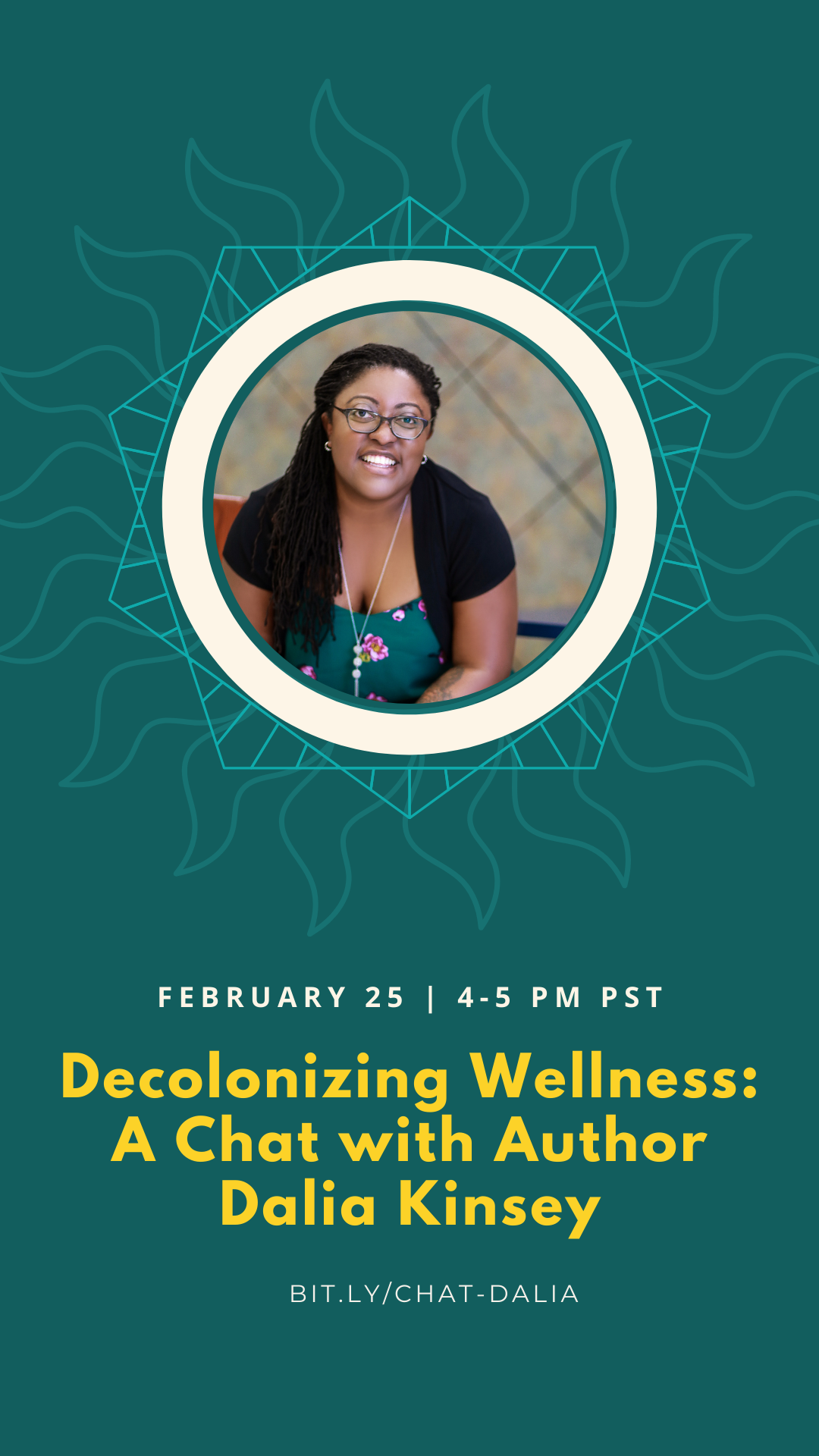

Instant replay: Decolonizing Wellness with Dalia Kinsey

Please join me and Dalia Kinsey to talk about Dalia’s new book, Decolonizing Wellness!

We explore:

» What called Dalia to write this book

» What “decolonizing” means when it comes to wellness

» Why there’s a need for wellness information specifically for non-white folks

» The ramifications of praising celebrity body parts, and more

◇─◇──« »──◇─◇

Dalia Kinsey is a registered dietitian, keynote speaker, and inclusive wellness coach with years of experience working at the intersection of holistic wellness and social justice in public and private sectors.

Dalia rejects diet culture and teaches people to use nutrition as a self-care and personal empowerment tool to counter the damage of systemic oppression. On a mission to amplify the health and happiness of BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ folks Dalia continually creates wellness tools and resources that center the most vulnerable, individuals that hold multiple marginalized identities.

Dalia’s work can be found at https://www.daliakinsey.com.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Lindley Ashline: Welcome everyone. This is Dalia Kinsey who has just published the book, decolonizing wellness, which is what we’re going to be talking about today. Not, not our cursed previous attempts. I promise we’re done with that, but but I am so excited to host Alya because.

[00:00:18] Getting to know Dalia and, and explore this work has been so exciting. And as someone who lives with white privilege myself it is such an honor to be able to elevate the voices of brown and black folks who are doing really important work, but don’t necessarily have the same opportunities and advantages that I have as somebody with white privilege.

[00:00:41] So I’m going to mostly be handing this over to Dalia. And I have some questions to guide us in our conversation. But, but this is, this is really Dalias time to shine, and I’m so excited to be able to offer that, that space. So Dalia, why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself your name, your [00:01:00] pronouns, where you live the work that you do in general and also where we can find you.

[00:01:04] And we’re going to revisit that at the end about where we can all find out his work, but go ahead and give us that.

[00:01:10] Dalia Kinsey: So my name is Dalia Kinsey. I’m non-binary I don’t use any pronouns. So just Dalia and I am in Griffin. So this was originally Cherokee land and that’s not it, but that’s the only group of people who’s coming to mind right now.

[00:01:28] Of course the head of the trail of tears is kind of close to here. So a lot of people were displaced. I am trying to remember what else was supposed to be in my intro and your. Yes. Yes. Yes. So I’m in the deep south and I’m just super excited to have an opportunity to bring this messaging to more people, because this is not something that ever would have been available.

[00:01:55] When I was a kid in the eighties and nineties, there [00:02:00] wasn’t any affirming information available for queer folks. And honestly, for black folks, there just was no such thing. So thank you for having me.

[00:02:12] Lindley Ashline: So what work do you do? Like in a general sense before we get into talking about the books specifically and where can we find you and the work that you’re doing and by the book.

[00:02:21] And so.

[00:02:22] Dalia Kinsey: Okay, thanks. So I am a registered dietician, but a holistic weight, neutral dietician. So that basically means none of my interventions ever focus on weight because being in a larger body is not problematic. That is just socialization. And I mostly right now am working with people through group coaching a lot of onsite wellness, public speaking, that sort of thing, because I found whenever I try to do one-on-one, I cannot seem to escape people who secretly just want to diet.[00:03:00]

[00:03:00] Even if they’re wanting to be more comfortable with their bodies. One-on-one just draws people who are not there yet. And it’s really. Difficult for me to navigate those types of relationships with somebody who’s at their very beginning of body positivity or questioning the patriarchy or doing any kind of liberatory work.

[00:03:25] That’s just not my passion. That’s not my target. So I’m pulling away from the one-on-one. You can find the book anywhere books are sold. So all the big stores like Amazon Barnes and noble Books-A-Million, but the easiest thing to do is just go to Dalia kinsey.com/book, and you’ll see a lot of hyperlinks to places that you can buy it.

[00:03:48] You could also get it from a local bookstore if they don’t have it in stock, you can request it. And you also can just request it at a public library as well, if it isn’t

[00:03:57] Lindley Ashline: available. [00:04:00] And I also put that link in the zoom chat and that will of course accompany the recording is. So talking about the book specifically, decolonizing lowness who is the book for like, who is your, your core?

[00:04:17] Dalia Kinsey: So I sent her QT BiPAP. So that’s queer trans black indigenous and people of color because there really is nothing else available from a body positive perspective that addresses what it does to you to be socialized, to question the way you intuitively love others. And to question your value because you do not come in the right shade.

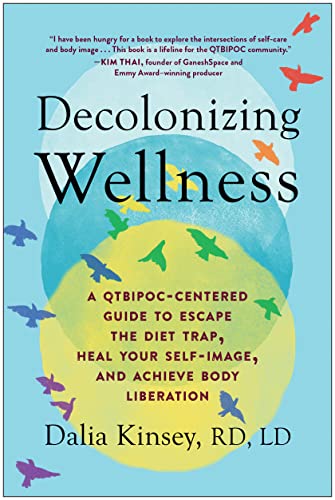

Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body Liberation

[00:04:43] So that is who is at the center of the book, but it’s helpful for anyone who is wanting to reevaluate their relationship with wellness without focusing on weight, because that is just, it’s not productive [00:05:00] and it really undermines your health to focus on weight. It shouldn’t, it doesn’t have a place in wellness, honestly.

[00:05:09] Lindley Ashline: So when you talk about. Wellness. And then you talked about health for you specifically, the way that you use those words, are those basically synonyms for each other? Or do they basically mean the same thing or do they mean different things?

[00:05:23] Dalia Kinsey: You know, that’s a good question. I think for me, it’s not the same thing, because I would say my health has kind of like iffy because I have some autoimmune issues that are basically genetic and I don’t think I’ll ever be considered a healthy person.

[00:05:42] I have disabilities related to mental health. So according to other people’s definitions, I’m not the picture of health. And honestly, if I could make some changes, I wouldn’t have opted to have any auto immune disease, [00:06:00] but wellness is more of the full picture to me. Like how are my relationships? How many times am I laughing in a day?

[00:06:09] Do I feel like myself? When I go out in the world, am I partnered with somebody? I really enjoy. Just do I feel good? To me, that is where I’m coming from with wellness and health. It feels a little more clinical. So health, maybe you can work with whatever conditions you have, but there probably isn’t that much you can really do to me.

[00:06:34] Wellness is the part that you have control

[00:06:36] Lindley Ashline: over.

[00:06:39] Dalia Kinsey: Oh, that’s really interesting in my head.

[00:06:42] Lindley Ashline: Yeah. Yeah. I really like, and I couldn’t tell you you know, what the, the sort of dictionary definition, the, the official definition, I couldn’t tell you what the CDC considers to be the Def the definition of health or wellness, but I really I’m really [00:07:00] intrigued by this concept of wellness, being the parts that are within your control.

[00:07:04] So how did you you know, as a dietician as you know, because it’s your life experience That is a world that is very focused on health and on wellness for various definitions of wellness and on, in very invested in diet culture. So how did you get from whatever your standpoint was when you went to school for this?

[00:07:29] Like, what was your journey like from that point to writing a book that sort of rebelling against a lot of. That world and that worldview

[00:07:40] Dalia Kinsey: as a kid, I always felt like a budding feminist, which is not cool in Georgia in the eighties. That was like radical to think that maybe people assigned female at birth should have equal rights, but you know, things got better early 2000.

[00:07:58] So [00:08:00] when I was in school, I wasn’t putting together that feminism and diet culture. Nick’s if you’re really paying attention. So I was pretty snowed thinking that everything that was being taught was accurate initially that this obsessive focus on having a BMI within a certain range was actually appropriate.

[00:08:25] But the deeper I got into my studies, the more obvious it became that the biases that they had were everywhere, it was in a classroom, it was in the textbooks and the biases that were easier for me to identify, because I knew that. False based on my lived experience was all the racial bias. Like all the assumptions that black people are too dumb to be able to feed themselves, which is not an exact quote, but that was the gist and all these assumptions that all black people in the United States have a homogenous food culture, which is ridiculous.

[00:08:59] [00:09:00] Even in the classrooms that some of these discussions were happening in. There would be me from the Southern United States, half of me anyway, and the other half is half Cuban and half to make end. So even right there, that’s like three different food cultures that influence how I eat. And the other person in class was from God.

[00:09:21] There’s one more who self identifies as black, who was from the Dominican Republic. And when we would ask, what do you mean? Who, what type of black people, what are you talking about? And it was beyond our peers, comprehension that we were not homogenous. And rather than listening to what we were trying to say, they just kind of rolled their eyes and continued the discussion.

[00:09:44] And so I started to think, well, if they’re all wrong about this and they’re taking it, like it’s fact and writing notes and ignoring the lived experience of everybody in the room, I really shouldn’t be believing everything they’re saying without questioning it. And from [00:10:00] there not so much believing in them and getting totally burned out on the obsessive focus on weight and how many of my classmates clearly had untreated eating disorders.

[00:10:11] Some of them did disclose that they had treated eating disorders. I don’t know why they would choose to work in such a triggering. Field, if they’re still working through that, but starting to see that people were prescribing disordered, eating to people who are fat while only getting concerned about the thin people when they were at death’s door really made me question, like, is anything that they’re doing here going to help anybody health wise.

[00:10:44] And by the time I finished and graduated, I wondered if that was even what I wanted to do. I was so burned out on the racism and the fatphobia. I wasn’t sure. That there was any way I could use the degree, that would feel right to me. [00:11:00] But then I thought, well, you know, public health feels more neutral. It’s not going to be focused on weight management.

[00:11:07] I thought we’re going to actually be using science. That’s one of the things that’s the most irksome about dieticians is that they’re always saying the difference between us and a nutritionist who isn’t a dietician, is that everything. Evidence-based that’s the story, but you know that there is not evidence to support dieting as a health intervention.

[00:11:32] It doesn’t make sense that it’s being recommended. Any other thing that you recommend to people? It has to be backed and you show that there’s some efficacy. We see that by and large dieting does not work for anybody over the longterm. So then why do people keep recommending it? Like it’s even a thing.

[00:11:49] Let’s assume that like, the fact that fatphobia damages your health, because it adds to your stress and it adds to discrimination and it limits your access to equal [00:12:00] healthcare, ignoring all that. Still. If it doesn’t work for more than 1% of people, how is that a recommendation like ever. So I just got burned out on how the messaging they were putting out there to students was so inconsistent with what they were doing in practice and seeing all the conflicts with.

[00:12:26] Who they’re kind of in bed with from a sponsoring standpoint, and just seeing that it was all really just about making money. As most things are not really about health and that even in public health, again, it’s just about maintaining the status quo and keeping the systems running, not really about anybody’s health and the fatphobia there.

[00:12:50] Honestly beyond disgusting. And there were times when it just gave me such rage that I didn’t know if I would [00:13:00] come back the next day, like forced weigh-ins for employees. Counseling people on weight loss. It didn’t ask for any counseling on weight loss and harping on it and wanting to weigh people at every staff meeting who does that.

[00:13:20] And all it ever did was stress people out that did not improve anybody’s health. And you could see people gaining more and more. Probably eating as a coping mechanism in that extremely fat phobic atmosphere and even people that were considered healthy according to their BMI were terrified of gaining weight, because it was so clear that everybody was watching you.

[00:13:46] And that the assumption was the bigger you are, the dumber you are, because if you have this degree in nutrition and your body’s still large, then the story is you must be some kind of dummy [00:14:00]

[00:14:01] Lindley Ashline: and you have talked in, in our, in our previous cursed attempt to have this. And, and in other contexts before that as well talked about.

[00:14:09] I believe you, you identify as a small fat person and for folks who aren’t familiar with that, that term there are, there’s an informal set of what we call Fattah Gories. That is that are a way to a way for us to be able to talk about levels of privilege where we might say for example I, my body is larger than Dalias and, and so I have a lower level of size related body size related privilege there.

[00:14:37] And so, so my body is on the edge between the large fat and super fat. And if you Google for the word fat Gories, you will be able to see some articles about this and talk about this. Some people choose to use these words and some don’t neither is right or wrong. But, but my point about this is that.

[00:14:53] Dalias body size was still probably quite a bit larger than the average dietician

[00:14:59] Dalia Kinsey: [00:15:00] to 100%. Some of that, especially considering how common it is for a lot of these defaults to have eating. I mean, I’m talking visible color bones, just criticizing each other. When they went from like a size six to a size eight, just a lot of toxicity.

Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body Liberation

[00:15:21] And I back then was like 50 pounds lighter than I am right now. We’re still way too big for them. So yeah, it was a very toxic atmosphere. And at the size that I’m at, yes seats on airplanes have gotten tight, but I can still get in them. And, you know, I don’t necessarily have to have a chair that doesn’t have arms.

[00:15:42] So my experience of discrimination as being a larger person is nothing like what I’ve seen other people experience. But when you are a fat dietician, you get a lot of blow back and undermine me as part of the reason why I [00:16:00] don’t work in a clinical setting because I had people say to me a couple of times in public health, you know, what, why, how are you doing nutrition, education look at you.

[00:16:11] And that was 50 pounds ago. So that was just not the scene for me

[00:16:18] Lindley Ashline: and something I want to touch on really quickly too, is back at the beginning of. Our discussion today, I talked about having white privilege. And now just now I’ve talked about having less size privilege. I want to touch base really quickly on the concept of intersect intersectionality, right quick for folks who may not be familiar with that.

[00:16:37] There’s a good chance that, that if you’re watching this recording, you already know that concept, but just in case because this is really important in the context of what Diane is talking about here. And talking about decolonization, which we’re going to get to here in a second intersectionality is the, the concept.

[00:16:53] And, and if you I, this is something that I also advise Googling because I don’t have the definition in front of me. But it’s basically the [00:17:00] concept that the more marginalized or oppressed groups you belong to the more those oppressions stack up and the less privilege you have overall. So for example, if Dalia and I both went to the same.

[00:17:14] I might be treated worse based on my body size, but I might actually be treated better because I’m white. So, so I have that specific marginalization that I’m in a very large body size. But Dalia is both in a large body size and black and queer, and those things all add up and they intersect with each other over, over time and over interactions.

[00:17:38] And so so I want, I want everybody to be holding this in mind as we talk about levels of privilege and how they interact with each other. And also, I didn’t think to say it earlier, but we will have some time for questions at the end. So so if you have questions as we go go ahead and type them into the chat or you can hold them until the end.

[00:17:56] And we’re going to have a space to, to ask those if you type it into [00:18:00] the chat, I’ll ask that for you at the end, or you can just. And we’ll turn on everybody’s mics at the end. And you can, you can just ask but let’s jump to that decolonizing because I think that’s going to be a term that, that people may not be as familiar with.

[00:18:14] So what does decolonizing mean as a, as a very general concept? And then what does it mean for.

[00:18:21] Dalia Kinsey: So as a general concept, it’s about trying to reverse some of the damage that colonization has done to a lot of cultures. And in a lot of cases, it means reclaiming traditional practices that have been derided or seen as barbaric or Savage and understanding that these things have value.

[00:18:45] And it’s only through the lens of like supremacy that they have no value. And in terms of. Especially in the book, it’s about de-centering whiteness and de-centering these [00:19:00] colonial European heteronormative standards that are still influencing us now and are still the standards by which we are judging ourselves.

[00:19:13] And sometimes also very frequently the standards by which we are being judged. And even it’s interesting, I was thinking the other day, Whether or not, it was a good idea to write a blog post on traditional African religions and kind of reclaiming some of that. And I thought, oh, I don’t want people to think that I’m not science friendly or basically the thought came up was, oh, what if people think less of me?

[00:19:48] What if they think I’m uneducated or uninformed? Because I, you know, practice traditional African religions. And if you’re Christian in the U S you don’t ever have to worry [00:20:00] that someone’s going to think they know something about you, just because. You say something about your Christianity, but when it comes to things that are kind of outside, what’s been accepted, like if this is not a religion that was brought here by the colonizers, and you say you practice that people may think, oh, that’s all superstition.

[00:20:22] When in reality, when we look at all these belief systems, like faith is like a pretty nebulous type of thing that there was no more logic involved in one faith than another, from what I’ve seen. But through that lens, it feels less than, and then you’re less inclined to be open about it because you don’t want to be ridiculed.

[00:20:43] And then you may find internalized stigma where you’re kind of embarrassed to openly be different or to openly not be as assimilated as maybe you think you should be, or as you were trained to think you [00:21:00] should be.

[00:21:01] Lindley Ashline: So when that comes to. Health and wellness again, keeping in mind that those may not be exactly the same thing here.

[00:21:07] But, but decolonizing that I think there’s a real cultural feel in the United States today that health is health in the sense, in the sense that that numbers are numbers and, and we know that specific things, and again, some of this may be evidence-based and some of this may just be what everybody knows which may or may not be reality based, but there’s the sense that the, okay, well, up to us down to a certain point, you know, a lower blood pressure number is always better.

[00:21:43] The, that we, we know that, that a blood pressure reading in this specific range is the optimal. And so I think. I think there may be some resistance from folks to talking about decolonize and this, when, when, so much of what we think about as being health or [00:22:00] think about as being wellness, seems like it’s very objective.

[00:22:03] So, so what are your thoughts on that? And also what is maybe something specific? Cause you gave the, the, the religion example, which has really rich is a really great example because again, it’s not something we, we in the majority are really forced to think about until it affects us or until somebody brings it to our attention, but maybe something related to food or, or health markers or something that is, that reflects that white centering, that white supremacy that, that shows.

[00:22:36] Why this

[00:22:36] Dalia Kinsey: makes a difference. Yeah. There’s so many levels to that because even the fact that here in the U S we only seem to respect things that come to us through some kind of hierarchical. Lens, right. It has to come from an institution that’s been vetted and vetted institutions [00:23:00] in this country typically are still institutions founded by older, straight white men.

[00:23:06] You know, and if you’re doing something outside of that, oh, it’s not real. It’s not legit. It’s airy fairy. There’s not enough evidence to support it. But the truth of the matter is there’s plenty of things that we still don’t fully understand how they work. And that doesn’t mean they’re not beneficial.

[00:23:26] And maybe if you can’t sell it, there will never be enough research to validate that a certain intervention works. So there are some foods and herbs that have been proven to be just as effective as pharmaceuticals. We will. You’re not. See that information everywhere, because if it costs you like 50 cents to get it from the store, why would anybody tell you about it?

[00:23:54] Right? The way this country has been from its beginning is driven [00:24:00] by profit and that’s profit over people. So most of the things that we see, it isn’t necessarily that it’s just a fact it’s that there was somebody who wanted to fund that study, meaning that someone stood to benefit from it. People don’t just do stuff for shits and giggles, right?

[00:24:17] They do it because there’s an opportunity to earn money in relation to whatever you find. And addition to that, sometimes people are swayed to look for a specific answer because of where the funding is coming from. So all that to say, like all these things, oh, we have all this definite research. It’s like the other things that are missing, it could have just been a matter of, there was no financial incentive for you.

[00:24:45] To do the same amount of research. And especially when I think about just the way that people just don’t question some things that we’re still using as health markers, [00:25:00] like there is a different standard for kidney function for black people. Still, if you go to a dialysis clinic, you’re going to see like, well, what’s a normal GFR for black Americans.

[00:25:14] And then also there’s still people who believe that black Americans just tend to have weaker lungs. Now that is a belief that comes straight out of the transatlantic slave trade, but there is still a difference in how they will measure lung function in black people versus not white people. And just that belief that you can look at someone and know what.

[00:25:40] Genetic history is, is also totally coming through that filter of how race became defined in the United States and how you had to define, like what degree of biracial makes you still something. Property that [00:26:00] absolutely affects the assumptions that people are making. Because if you’re grouping all of these people together, based on one characteristic, skin colors, one characteristic, it is not linked inextricably to any other characteristic.

[00:26:12] So grouping people together based on skin color, it’d be like grouping people together based on eye color among white Americans. Would you believe that that makes any sense, like, oh, people with green eyes, they have poor lung function, you know, they’re kind of lazy, so it’s good that we get them out there working and don’t let them rest too much.

[00:26:33] They’ll never get up and do anything like, would anybody believe that? But we’ve heard it for so long. It feels like it’s real. And the weird thing about humans and the brain is that if you believe it’s right. In many ways, it starts to be real. So the differences in health outcomes have become real because we, as a society have made race [00:27:00] real and the disparities determine how your health plays out.

[00:27:04] But then some physicians really do believe it’s linked to actual genetics. And there’s also people with the queer layer, going back to the intersectionality there, a lot of older practitioners out there that were in the workforce when the DSM-V is that this is the right letters. I’m wondering when.

[00:27:29] There you go when it was still, I think I thought the S was a five. There were still people saying that homosexuality was a mental illness. So even though, you know, that’s no longer the case when people notice higher rates of depression among queer people, and they were trained at a time when it was classified as a mental illness.

[00:27:51] Well, then their assumption is most likely going to be that the queer. Comes before the depression and the anxiety instead of [00:28:00] that, the disparities cause anxiety and depression. So they’re going to assume that you can’t really get out of this because you’re supposed to be depressed because that’s what people like you are instead of them saying like, Hmm, let’s look at who you’re spending time around.

[00:28:16] How often do you feel safe in the course of a day? Where can you go where your queerness is a non-issue and if you have multiple marginalized identities, it’s really challenging sometimes to find a place where you can just be a human being. So you may go hang out with queer folks at pride, you will inevitably deal with some kind of racist microaggression.

[00:28:39] And if you go hang out with black folks, it takes up, I don’t know, 30 minutes before somebody says something homophobic. So. That is not being addressed in healthcare. The chronic stress that comes from being marginalized. [00:29:00] And if we know that stress tears, the body down, literally everybody knows that everybody knows someone who they are pretty sure died of a broken heart.

[00:29:08] You know, when you have one spouse go and the next person’s dead within five days, it’s a real thing. There’s even a word for that in Japanese people know that emotions do affect the way the body functions. So why would we think that ignoring chronic stress from racism, from transphobia, from homophobia makes any sense.

[00:29:30] If we’re talking about trying to help people live long healthy lives, how can you ignore that and then decide to focus instead on body size. It just, it doesn’t make any sense

[00:29:43] Lindley Ashline: that again, this comes back to intersectionality and how things layer. Yeah, because if you, the more like Dalia was just saying the more of these intersections that you have the harder it’s going to be for you to exist, to find spaces, to exist in [00:30:00] a where you’re not still getting random crap thrown at you because of who you are like Dalia was just saying, you know, if, if you’re in a group full of black folks and you’re getting homophobic stuff thrown at you or thrown around at you w where you’re still having to listen and absorb that, or if you are in a group of fat folks who are being abelist or, or whatever, and you’re, you’re both fat and disabled you’re, you’re getting, you know, more and more of these stress layers, and we know that stress affects the body.

[00:30:32] There’s, you know, there’s been, there’s a whole field of study related to this very famously, there is a book called the body, keeps the score. That that many, if you’re watching this and you are a healthcare provider, there’s a good chance that you’ve heard of or read this book. And it’s all about how the body holds on to trauma and displays that trauma.

[00:30:50] It’s also a very fat phobic book, which is really unfortunate. And that, and again, that comes back to these, you know, all kinds of things that we’ve [00:31:00] discussed, like what everybody knows about health. And because here’s this researcher who has done fundamental research, this, this is like, he created this whole field of how trauma is stored in the body, this whole field of study.

Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body Liberation

[00:31:13] And yet he’s willing to like this groundbreaking researcher who for at least one entire chapter falls back on what everybody knows about body size. And, and it was really shocking to run across that. When I read that book and it threw me out of the book, I never finished it, but, but coming back to. Coming back to download his book, we should not have a giant fat phobic chapter right in the middle of it.

[00:31:37] There’s a couple of specific things that I, that just caught me as I went through the book that I really want to want to ask Dalia about. And one of those is in chapter five where, where you’re talking about celebrities and, and celebrities being praised for specific body parts, like tone to arms.

[00:31:55] And as we talked about last time, the first person I think of when I think about [00:32:00] well-known public figures who were praised for their arms as Michelle Obama. But but it’s interesting because on a surface level, it sounds like celebrities being praised for their bodies instead of toned it and sort of turned.

[00:32:15] So what’s Friday afternoon and I can’t words anymore. I’m I’m out. I’m sorry.

[00:32:20] Dalia Kinsey: He can still remember things. Cause I keep feeling like in the middle of a sentence, I’m like, where was I headed? I know it’s the Friday.

[00:32:30] Lindley Ashline: So, so let me, let me, let me just try the whole thing again. So, so it seems like it would be a relief to see celebrities being praised for their bodies.

[00:32:41] As opposed to. There it is again, it’s the same thing. Torn down, not turned down, torn down. I’m sorry. I just, that

[00:32:52] Dalia Kinsey: word with our powers could buy, like, what was I trying to say? Diaz? I can say DSM. So [00:33:00] the way you can brainwash somebody, you can do it or control someone. You can do it with positive or negative reinforcement.

[00:33:08] So when you get positive reinforcement, it’s still training you it’s training you to prioritize or value certain things or to think, oh, this is how I get praises, how I get acceptances, how I can be worthy. And one of the things that I know as when I was younger, I was constantly being told. How beautiful I was, how stunning I was always getting stopped in the street.

[00:33:31] It was constant. Well, at the time it seemed neutral. Sometimes it felt like it was a little over the top or sometimes made me feel unsafe. But when I had the audacity to stop looking like I was under 20, the way the compliments dried up, well, then it was obvious that that wasn’t neutral. That was damaging because what if something happens to Michelle Obama’s arms and they’re not whatever they are right now anymore.

[00:33:59] [00:34:00] Like that could really be upsetting. It makes you maybe get attached to the way your body is in one moment in time. And the one thing you can count on your body to do is keep changing that that’s, it’s always changing. So to focus so much on the body could make somebody feel really nervous about.

[00:34:22] Changes and anyone else who sees that, that, oh, like Cameron Diaz. They like to pick her body apart to Jennifer Anniston. You see these women that, you know, are considered the ideal form of feminine body. According to the U S they’re white, their hair is straight they’re thin and they look like they come from money.

[00:34:52] If they can’t be fully acceptable, then what does that tell everybody else? Like, if they could [00:35:00] only have. Arms or their ankles are great, but they’ve got a weird toe that just trains you to pick your body apart. And then you create standards for every single part of your body, which is just going to lead to self rejection.

[00:35:17] And maybe some self-loathing because if you don’t see yourself as a full person, then you’re going to get caught on things like, oh, why is my arm this way? Why is my stomach this way? Why is this boob different from that boob? Why are the boobs, you know, acted like they know it. Gravity is because like all your body does is change, but it really makes it hard for you.

[00:35:41] The fact that you are more than your body to see that hyper-focus, that lets you know that to a lot of people, we are just our body and I don’t think that’s healthy for anyone. So it really makes you think when you’re [00:36:00] giving people praise, remember that none of that’s neutral. And so if you’re complimenting someone on like how beautiful they are.

[00:36:12] Is that helpful because they can’t control their beauty. They didn’t do anything to get it. And they don’t know how their face may change in the future and even going through COVID it’s been so interesting to see how people are, have realized only after losing some abilities, how attached they were to being able bodied.

[00:36:37] So you don’t know that. Really fixated on like how much people love your hair until it starts falling out. And you don’t know that, you know, it really means a lot to you and makes you feel worthy for people to like, I dunno your perfect face until it’s covered in recalls. You know? So it really is a message that they’re sending and you even see the [00:37:00] way by and large, the media throws these women away.

[00:37:05] Once they age don’t, you can’t even get a part anymore. You have to play grandma’s when you turn 30. And all of that messaging is definitely being received by every one of us, even when you try to ignore it. And you know, it’s trash, you know, it tends to get in there somewhere. Yeah.

[00:37:23] Lindley Ashline: Yeah. Just really quickly, I want to give an example of this.

[00:37:27] I looked at my hand, see the day I’m 41 and I was going to hold my hand up, but you’re going to be able to see it. It’s to fight. But I realized that at 41, the back of my hands, the skin is, is starting to be a tiny bit creepy. They call it creepy skin, like crepe, like the fabric that’s wrinkled.

[00:37:45] And and the first thing that flashed into my head when I noticed that in general, I’m pretty good with signup signs of aging. I’ve got like cool little gray streaks here. And, you know, I’ve got some cruise feet starting and I’m, I’m I’m into that. But I saw the back of my hands. And the [00:38:00] first thing that flashed into my head was sometimes when I clicked through and read a news article and there was those scammy ads at the bottom one that I saw a whole bunch a couple of years ago over and over and over was one of these, you know, one weird trick type type banner ads.

[00:38:15] And it was about crepey skin. And I didn’t even realize it at the time, but that got my. And, and when we see tabloids and TV shows and magazine articles and all this media over and over and over on a specific thing, like these celebrity body parts, like that gets into our head and it, and this was such an interesting example because something I wouldn’t have thought twice about otherwise I would have just been like, oh my skin’s changing.

[00:38:44] Cool. But suddenly it was like, all it was, all I could think about was, oh no, my skin

[00:38:50] Dalia Kinsey: is changing. It’s it’s, it’s just the, Nana’s like how things that people don’t even do to hurt. You [00:39:00] still have an effect on you. I noticed that I’m getting the, I can see the aging. It’s like the cleavage aging. And I don’t know why.

[00:39:09] I just thought that only happened to people who suntan a lot. I didn’t know that was for everybody, but now I know

[00:39:19] Lindley Ashline: now I’m like, oh, what’s going on?

[00:39:23] Dalia Kinsey: Looking looking 40. I turned 40 this year and it’s just been interesting, but it was easier to turn 40 than it was to turn 27. Cause I just felt like, wow, I can’t say I’m in my early twenties anymore.

[00:39:41] Like I’m exiting the age of everyone sees you as just like we’re staring at, which is weird because I felt like I didn’t even want to be stared at, but I didn’t not want to, you know what I

[00:39:58] Lindley Ashline: mean? [00:40:00] I mean, by the time I hit adulthood, I was already significantly fat. So I don’t actually know what you mean.

[00:40:07] Dalia Kinsey: And again, talk about

[00:40:09] Lindley Ashline: actions of privilege and the different types of privilege. Yeah, no, I just, I just got like everybody assumed I was a 40 year old mom from the time I was. That’s because I just got slotted into the matronly category right away.

[00:40:20] Dalia Kinsey: But yeah. And that is a real thing. Someone pointed this out to me.

[00:40:23] This is why it’s so important to have a diverse array of people in your life, because you will not notice things. A lot of times it don’t affect you unless they’re crazy blatant, because I hadn’t realized someone mentioned to me, oh, they don’t make clothes for women. 35 and up. And I was like, what?

[00:40:45] Somebody said this to me when I was in my twenties. I’m like, that doesn’t make sense. Like they’re women 35 and up everywhere. Of course they’re wearing clothes. They got them from somewhere. But you can tell, like, they’re not cut for the way the body tends to change the way, you know, as your hormones change, when [00:41:00] you get older, the places that the adipose tissue tends to go, you’ll notice clothes don’t fit.

[00:41:07] Like they used to. I mean, I remember a time when every time I went to the store, everything fit exactly the way it did in the picture. But once you get to a certain point, they’ve just decided not to make room for us or acknowledge our existence by and large older fem presenting people are invisible in this patriarchal system.

[00:41:32] Lindley Ashline: And sometimes that’s useful. I don’t get, I don’t get catcalled when I’m invisible. So, so, you know, and I don’t, it also means dudes will randomly cut in front of me in line because. Because they literally can’t see me. It’s like, I don’t exist. Wow.

[00:41:47] Dalia Kinsey: But you know what? I don’t know. But I feel like that might be disrespect reserved for white women because I’ve seen that happen.

[00:41:57] And I don’t know what that’s about. [00:42:00] No one has ever done that to me. Maybe because they’re afraid, like the stereotype is that people are

[00:42:09] Lindley Ashline: grabbing your fingers up something sassy,

[00:42:12] Dalia Kinsey: but is my head around. Yeah. So maybe that’s why,

[00:42:16] Lindley Ashline: I don’t know. Well,

[00:42:18] Dalia Kinsey: you never know why you’re being treated poorly. Like there’s a lot.

[00:42:22] Yeah,

[00:42:23] Lindley Ashline: yeah. Yeah. So it’s something for us to explore another time. Cause as much as I would love to just make you talk to me for the rest of the evening, we’re we’re about ready to start wrapping up, but really quickly. Another thing that I saw as I was reading, and I don’t remember which chapter this was in, so.

Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body Liberation

[00:42:38] So you’ll all have to find it as you go through your own copies. But you talk about the term hunger trauma, and that was something that, that really was resonant, but that I had never heard before. So really quickly, can you, can you go into talking about what, what that means and what the ramifications might.

[00:42:58] Dalia Kinsey: Yeah. If you go [00:43:00] through periods of time as a child where you have to be hungry, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re neglected. It doesn’t mean you weren’t fed three meals a day, but when you’re having lots of growth spurts, sometimes three meals a day, still gonna leave you hungry. And if you’re in a lower income working class family, there might not be money for extras and for snacks.

[00:43:23] So you get accustomed to when there’s food available, especially free food. That’s a huge trigger for people. You eat as much of it as possible because you don’t know when you’re going to get to have like unlimited access to food again. So you go to a party, you eat the whole time and you see kids doing this.

[00:43:44] There’s a big difference. I mean, you can see it right away between a child. Who’s able to like free graze all day and a child. Food is being controlled tightly. There are lots of different ways that people end up having that hunger trauma. It could be a [00:44:00] parent. Who’s not allowing the child to lead the feeding process or could be people who just literally don’t have the food.

[00:44:07] I grew up in a family of five. Both of my parents were there. They were good parents, but we were on a pretty limited budget. So yes, we ate three times a day, but there usually wasn’t enough for seconds or at least not everybody could have seconds, but the person who got to have seconds was whoever finished first, because in theory, that must’ve meant you were the hungriest and you needed.

[00:44:32] What that really trained us to do was to eat as quickly as possible so that we would get seconds. And if you tell somebody who’s been through that to diet, then you’re asking them to put their body through that same. Sensation of not being enough and not knowing, not having enough and not knowing when the next serving a food is coming.

[00:44:59] And that’s [00:45:00] absolutely going to trigger binges and out of control eating. And the thing that sucks about bingeing is a generally, it makes you really uncomfortable. It hurts and it’s not satisfying. And ideally when you eat food, it should delight you or energize you or soothe you. It shouldn’t hurt you.

[00:45:21] But when people encourage you to restrict, after you endured involuntary restriction, that’s going to make it impossible for you to have a peaceful relationship with food.

[00:45:34] Lindley Ashline: So I have two more questions, really, really, really quick. And then we’re going to get to, to our Q and a. So think about what questions do you have for Dalia.

[00:45:43] And again, you can pop those in the chat or at the end, I’ll open it up and you can ask yourself. Next to last question. This is my favorite question to ask people, because it’s always, it’s always so different. What do you personally like to eat for

[00:45:56] Dalia Kinsey: breakfast? I’m going to stick with seafood. Like [00:46:00] the first time during our, you know, rough recording.

[00:46:03] I was thinking like eggs Benedict with salmon or shrimp, but then I realized also fried fish and grits like that to me. That’s breakfast. Oh,

[00:46:18] Lindley Ashline: okay. Okay. Oh no, I want grants. All right. And finally just remind us one more time where we can find you and by the

[00:46:28] Dalia Kinsey: way, Go to Dallas. Woo Coda, Dalia, kinsey.com/book, unfortunately social media and I just, we’re not jelly.

[00:46:40] So the best thing to do is to jump on the newsletter. That’s the easiest way to keep in touch with me. And when you hit reply to anything I send, then, you know, I, it goes straight to my inbox. I read all my emails. So that’s the best way to keep in touch with me. Pretend it’s the nineties. [00:47:00]

[00:47:00] Lindley Ashline: I would like, I would like to subscribe to your newsletter.

[00:47:03] Dalia Kinsey: Yes, exactly. I’ll put that in the chat as well. I just moved to south stack. I don’t know if everybody’s using it, but so far, I really like it. And I’m going to have all kinds of cool content on there for real this time. So

[00:47:19] Lindley Ashline: feel free to unmute yourself and ask your questions and I’ll give it. A quiet 30 seconds here.

[00:47:28] And let you let you ask anything you want to ask and then if nobody has anything, then I have another question

[00:47:42] Dalia Kinsey: that gives me time to yeah.

[00:47:48] Lindley Ashline: When I click on that too, while I’m thinking about it. So I have it open.

[00:47:55] Oh yeah. Put the book link in there to you.[00:48:00]

[00:48:10] Dalia Kinsey: and what a difference Friday next to a cognitive function?

[00:48:16] Lindley Ashline: Yeah, this is, this is that, that coasting into the end, this this point. All right. So if you have any questions that come up for you later, or if you were watching the recording, you can check the links and ask Dalia directly. I have one really silly question to wrap us up with is that plant real?

[00:48:33] I’ve been

[00:48:34] Dalia Kinsey: tying to that. So embarrassing. No, it is not. I have such shame about my artificial plants because I just keep killing all my plants I do right now. I have lucky bamboo. I know that’s not the real name, but the scientific name is too complicated for me. I’m alive on my desk, but half of it has turned yellow.

[00:48:58] I don’t know why I’ve read [00:49:00] that. It could be fertilizer burn. That’s what I’m hoping in the future that I can be a plant long, like you and all the other plant people.

[00:49:11] Lindley Ashline: No, I feel like I was an unintentionally flexing on, you

[00:49:14] Dalia Kinsey: know,

[00:49:19] Lindley Ashline: where you can’t see as the dine plant on that blue bookshelf behind me.

[00:49:24] Dalia Kinsey: Well, at least I know sometimes it happens to you too. I don’t know why, like plants, I love green and I love being out in nature, but once I bring that stuff inside, it doesn’t last

[00:49:37] Lindley Ashline: long. I’ve just killed so many that eventually I figured out how not to kill a lot of them.

[00:49:41] That that’s all.

[00:49:43] Dalia Kinsey: Yeah. Just don’t give up and that’s it good. That’s such a good point. I think we’ve mostly been trained to think if we’re not good at something right away that it’s not for us because that’s kind of how. Train you in school, you have exactly one semester to learn it. And if you’re still getting asked, then [00:50:00] forget it.

[00:50:00] You’ll never get it, which is not true. Some of us probably just needed more time. So yeah. I need to adjust my, the way I’m looking at this plant thing. Yeah. And

[00:50:11] Lindley Ashline: honestly, big plants like the, the fake one that’s behind you. There, they take a ton of light, a ton of tension. I mean, depending on the plant, you know, there’s, they take a lot of resources.

[00:50:25] And then honestly, one of the reasons that I have a whole bunch of plants behind me that you can’t see, and I, I totally staged these two. These are real, but they belong in my bathroom. They don’t stay here because there’s not enough light right here. Cause I know it looks like there’s a lot of light coming in the windows, but it’s not actually a very bright room.

[00:50:42] So,

[00:50:43] Dalia Kinsey: so those don’t want to love the idea of plants in the bathroom. That sounds wonderful.

[00:50:48] Lindley Ashline: I also can’t see all the ones that are ratty, like. This one is farther behind because it’s got some bratty leaves on it and you can’t see them because they’re on a focus. So,

[00:50:59] Dalia Kinsey: okay. [00:51:00] That helps. That helps. And it actually, it’s pretty good that you thought it might be real as a plant person.

[00:51:09] So that makes me feel a little better.

[00:51:12] Lindley Ashline: I mean, it’s green. It looks good. What does it matter? I was just going to be super, super impressed if it was,

[00:51:23] Dalia Kinsey: and I turned it around. Okay, good. Melinda Oakland feeling my pain. Oh yeah. I need to get a friend who wants to come help me with class. I actually live in a 55 plus community.

[00:51:35] I probably could just go outside and ask literally anybody. Oh yeah. I’m always trying to teach people stuff around here. I need to

[00:51:42] Lindley Ashline: like. I will tell you, I will come in and water. These plants

[00:51:49] let the retirees

[00:51:50] Dalia Kinsey: help. Yeah, I really need to. I’ve been so consumed with all this other personal development work has, I will say when you’re trying to change your [00:52:00] relationship with your body. Oh boy, it takes time because we’ve spent our whole lives being told to reject ourselves. Yeah.

[00:52:10] Lindley Ashline: And it takes effort and resources to you just like, just like dieting.

[00:52:15] It takes resources and effort. In the, I mean, hopefully, hopefully as you untangle those things and stop dieting you know, it will take you fewer resources, but, but healing takes resources. And like if you’re spending, I don’t know, let’s see an hour a week in therapy and you are. You’re reading, reading a couple of books on, on anti diet principles and you’re reading decolonizing wellness.

[00:52:36] And you are, I don’t know, doing those things. You may, may not have time to take care of a big old tree. This is true. Now you thank you so much both for your time today and for, for doing this a second time. I’m so I’m so grateful to have your time a second time, both so that we can give people a good recording this time to watch later.[00:53:00]

[00:53:00] And just to have your time again, it was really

[00:53:03] Dalia Kinsey: easy, so much. I really appreciate your support. This is it’s always so fun talking to you.

[00:53:08] Lindley Ashline: Ah, you too. All right. Thank you so much for everybody who was able to attend. We had one person who needed to leave earlier, and I don’t know if you saw it in the chat, but they, they said that they that they were really enjoying it and just had to pop out earlier.

[00:53:20] So we’ll make sure everybody gets a recording here somewhere between a few days and a week from now. And and if you are watching the recording later, thanks for taking a look. And I will also put this up on the blog and on YouTube. So you’ll be able to find it everywhere. And I hope everybody has a good evening.

[00:53:38] Thanks again, Dalia.

Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body Liberation

Hi there! I'm Lindley. I create artwork that celebrates the unique beauty of bodies that fall outside conventional "beauty" standards at Body Liberation Photography. I'm also the creator of Body Liberation Stock and the Body Love Shop, a curated central resource for body-friendly artwork and products. Find all my work here at bodyliberationphotos.com.